Friday, December 24, 2010

In God We Trust; All Others Pay Cash!

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

ePublishing for fun and profit with WalrusInk

We love publishing

We love publishing

The WalrusInk partners are all experienced publishing professionals. Not only is it an industry we know well, it's something we love doing. For us, ePublishing is an opportunity to do what we love without the heavyweight burdens of old-fashioned publishing we feel are crushing the industry into oblivion.

We love technology

As much as we love publishing, we are also passionate about technology. ePublishing involves rapidly changing technologies that are ushering in a genuinely new age of publishing. While the publishing status quo sees these changes as a threat, we recognize them as a remarkably exciting opportunity with unbounded potential.

We love paradigm shifts

We see ePublishing as providing a fundamental shift in the way knowledge is shared, which is a pretty big deal and something we'll likely write about at greater length in the future, but for now, you'll just have to take our word for it.

We love authors

And finally, we love working with authors. We learn so much from our authors and it makes us proud to be able to help hone, clarify, and ultimately publish their work and make it available to buyers, the seekers of knowledge, our loyal customers.

WalrusInk: friend of authors, foe of tyranny!

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Pricing eBooks—Logical Assumptions Need Not Apply

There's really no consistent logic to how eBooks are currently priced. Publishers want prices higher to increase profit margins. Amazon wants prices lower to encourage increased sales volume. Apple wants prices more standardized, because that's just the way Apple does things. There have been reports of eBook editions selling for higher prices than printed editions, which makes little sense except that some publisher has decided that they can make more money this way. There have been reports of Amazon capitulating to publishers' demands to raise eBook prices, followed by reports several months later of Amazon forcing publishers to sell their eBooks at lower prices.

There's really no consistent logic to how eBooks are currently priced. Publishers want prices higher to increase profit margins. Amazon wants prices lower to encourage increased sales volume. Apple wants prices more standardized, because that's just the way Apple does things. There have been reports of eBook editions selling for higher prices than printed editions, which makes little sense except that some publisher has decided that they can make more money this way. There have been reports of Amazon capitulating to publishers' demands to raise eBook prices, followed by reports several months later of Amazon forcing publishers to sell their eBooks at lower prices.

There's not much clarity to be gained by watching the big boys try to bully and bludgeon each other over pricing. WalrusInk pricing will attempt to establish a price that is fair to consumers and provides a reasonable profit to our partnership of editors and authors so that we can earn a reasonable living. We have attempted to model this with some assumptions about volume and velocity, but there's very little history on which to base our assumptions. One ends up with a set of variables that is larger than the set of constants, which is akin to looking at the stars to predict the future only to find that there are ever more stars and no predictable future.

Nonetheless, the eager-beaver budgeteers at WalrusInk have decided to base our model on a standard eBook price of $9.99. We could build a numerical model to justify this decision, but in the end, it seems like a fair and reasonable price from just about every point of view. It's easy to imagine that some of our shorter eBooks will sell for less, but we're more likely to want to split a book into two parts than go for a single book at a higher price. Why? That's a discussion for a future blog.

Friday, December 3, 2010

The End of Words, or South-Bound Dictionaries

I wrote this last year, Thanksgiving 2009, though why I never posted it is unclear: sloth, forgetfulness, doubt, the usual excuses of an unfocused mind. But I find my work in this case to be of a timeless nature, so I'm publishing it now.

Twas the day after Thanksgiving, and all through the house, not a creature was stirring, except in the living room. The stockings were hung by the fireplace with care, in hopes that they'd dry out, because it was raining.

Twas the day after Thanksgiving, and all through the house, not a creature was stirring, except in the living room. The stockings were hung by the fireplace with care, in hopes that they'd dry out, because it was raining.

We are all reading: Katharine is halfway through Wolf Hall, a 700-page fictionalized account of Henry VIII that recently won the Man Booker Prize. Marian has a script from her friend, Edward Albee, and she's busily underlining with a yellow marker. Wells has left the room to tend to the roasting sweet potatoes and spend some quality time with his chemistry textbook.

I am browsing, rather than actually reading, through the Apple iTunes store for anything having to do with Portugal in general or Lisbon specifically. There are travel apps for guide books, maps, and language study; audiobooks, a walking tour of Lisbon and a recently published book about the great earthquake, tidal wave, and fire of 1755 that is referred to by Voltaire in Candide; and there are lectures from iTunes U. that touch on matters Portuguese from numerous angles, including matters economic and political.

But it is Katharine who brings up the subject of zymurgy—actually, the discussion is focussed on the word rather than the subject. There it is, right in the middle of a paragraph, in the middle of the page, in the middle of a chapter, in the middle of Wolf Hall. I've looked it up, now.

zy·mur·gy (zī'mûr'jē)

n. The branch of chemistry that deals with fermentation processes, as in brewing.

So says the American Heritage Dictionary, and Katharine remarks that it is just like the word "enzyme." She can make these rapid word associations because she's studied both Greek and Latin, though only Greek matters in this case. But then follows this gem of randomness; a fact so trivial and yet so profound, that I barely know what to say, except that I shall treasure this bit of knowledge and use it in conversation as often as possible.

The following I quote in it's entirety from dictionary.com by way of the Online Etymology Dictionary.

Word Origin & History

zymurgy

branch of chemistry which deals with wine-making and brewing, 1868, from Gk. zymo-, comb. form of zyme "a leaven" (from PIE base *yus-; see juice) + -ourgia "a working," from ergon "work" (see urge (v.)). The last word in many standard English dictionaries; but in the OED [2nd ed.] the last word is zyxt, an obsolete Kentish form of the second person singular of see (v.).

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

The Transition Manifesto: Revolution or exaggerated idealism?

I have written a Manifesto for WalrusInk. It's several paragraphs long, but in essence, it boils down to:

WalrusInk: ePublishing friend of authors and foe of tyranny!

WalrusInk: ePublishing friend of authors and foe of tyranny!

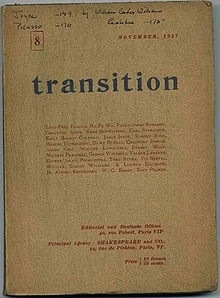

We don't talk seriously about manifestos and tyranny these days, but I'm attracted to the revolutionary fervor of these words. And then I was talking on the phone with my friend, Kenny, and he started talking about one of his former students who wrote a masters thesis about Transition Magazine and Marcel Duchamp. I had never heard of Transition Magazine, so while we were talking, I looked it up in Wikipedia, which is where I live a good deal of my online time.

"Transition was an experimental literary journal that featured surrealist, expressionist, and Dada art and artists. It was founded in 1927 by poet Eugene Jolas and his wife Maria McDonald and published in Paris."

I had discovered an example of 20's radical idealism that somehow wasn't included in my studies of utopian architecture and planning from the period. This was pure art for art's sake as a means to save the world. None of the semi-concrete "machine for living" or "contemporary city" idealism of Le Corbusier and his followers. But either way, weather you build it of words or wood, there's something quaint and naive about 20s idealism, especially in light of history, which pretty much goose-stepped all of that creative energy, turning it into hatred, war, and oblivion; a bitter irony.

"The journal gained notoriety in 1929 when Jolas issued a manifesto about writing. He personally asked writers to sign "The Revolution of the Word Proclamation" which appeared in issue 16/17 of transition. It began:

"Tired of the spectacle of short stories, novels, poems and plays still under the hegemony of the banal word, monotonous syntax, static psychology, descriptive naturalism, and desirous of crystallizing a viewpoint... Narrative is not mere anecdote, but the projection of a metamorphosis of reality" and that "The literary creator has the right to disintegrate the primal matter of words imposed on him by textbooks and dictionaries."

Like Transition, we welcome new ways of approaching old problems and see this as a timely and necessary part of the general dissemination of knowledge. What gives this the flavor of a revolution is the resistance of the status quo to change, which explains why WalrusInk has chosen to go outside of the status quo to adopt the new models made possible by electronic publishing, pervasive computing, and a lot of forward-thinking writers.

Viva la WalrusInk manifesto! Sic Semper Tyrannus, and viva la revolution!

Thursday, April 8, 2010

iPhone OS 4.0 Press Conference Summary

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Personal History: On Turning 50

April 30, 1952

The burden of turning 50, a remarkable if not unprecedented event. It is as remarkable and ordinary as the day of my birth, April 30th, 1952. The young mother, Amelia, aged 27, experiencing her second birth in less than two years. “Twilight sleep” was the common practise for hospital deliveries then, thus saving the mother from at least a portion of her own experience. The young father, Reubin, almost 29, having attended numerous, though not many, births as a medical intern and resident, had a doctor’s authority to attend his own son’s birth at the old Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

The parents’ experience of my birth date me as assuredly as the political events of the day. Truman, a baby of the 19th century, was still president. Can my own children believe that I have lived through 11 presidents and the entire cold war? This should qualify me as something of a veteran, but it in no way defines me; no more than my age.

I do not remember my other remarkable birthdays. The turning of 10, 20, 30, and 40 bring back no special memories of grand celebrations or events of note. I remember a birthday party when I turned seven. We had recently moved to the house where my parents still live. I remember a sunny, mid-spring day and an underfurnished house. My friends, Jan Frisky, Jay Gouline, Hugh Hayes, Stevie Wexler, and Bruce Daniel (who alone remains a friend), joined the celebration of Russian tea, carrot sticks, and strawberry shortcake. Did we have hamburgers and hot dogs? I don’t remember.

It’s not possible that this was my only childhood birthday party, but none of the others left any sort of impression on my memory. There are movies of my older sister Julie wearing a tutu for her sixth birthday at the old house on St. Dunstan’s road. There was pin the tail on the donkey and musical chairs, my father had a brand new, pre-stereo, hi-fi, and he controlled the lowering and lifting of the tone arm on the turntable. It might have been a recording of Benjamin Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra on a 78 RPM, long-playing record.

If my two younger brothers had birthday parties, I have only the vaguest memories of them. Laurie, one year younger, favored chocolate ice cream and managed get it on his person in the most unlikely places, behind the ear being one that lives on in the family lore. I remember baby Tommy, only three years younger, but the baby much past his infancy, experiencing cake and ice cream for his first birthday. He had a low baby table with a seat practically in the middle of it. There was plenty of room to spread birthday dessert all around in typical one-year-old fashion.

Age 13 was surely important for most of my friends, who celebrated with Bar and Bat Mitzvahs followed by luncheons and dinner dances. I remember many of the individual parties of that year, but not my own. I shall never understand the significance of “sweet 16.” I suppose it is a debutante thing, because only girls had a fuss made over their sixteenth birthdays. I assuredly made none made over my own.

When I turned 19 and was freshman at college in St. Louis, I remember my mother sternly reprimanding me over the phone for a lack of achievement and a complacent manner. I don’t know why she felt called upon to rebuke me on my birthday. I’m sure it is not something she would like to be reminded of. I was in architecture school, a place I had wanted to be for many years, but a place that brought me no pleasure or satisfaction. In my memory, it stands as my worst birthday. Could any others have been so disastisfyingly gloomy? I don’t think I wept, but there was no sense of pleasant satisfaction on that day.

18 was a more momentous anniversary. For the first time, one could both vote and drink at age 18, and there was the sense of insobrietous power. That was 1970, my senior year of high school, and the headlines for my birthday were punctuated by President Johnson’s bombing of Cambodia, which brought about the subsequent shooting of students by the National Guard at Kent State, a fateful turn in the ill-fated war in Vietnam and anti-war protests. My first presidential vote was cast for Hubert Humphrey, a personal acquaintance of my parents who had been friends with his sister, whom I remember as a large, brassy, smoker married to another Hopkins doctor.

I have no recollection of my second birthday in St. Louis, number 20, and nothing significant remains with me from my 21st birthday celebrated in Bennington, Vermont. However, among my few memorable birthdays, the 22nd, still in Bennington, is perhaps the best remembered. A few of us went to a Japanese restaurant outside of town. There were five of us: my brother Tom, then in his first year at Bennington; David Shorey, who became a dealer in antique flutes and is now a fugitive living in Amsterdam having been convicted of felony possession of Marijuana charges in Maine; Raymond Gargan, who has remained a friend and has also become a professional colleague, and Katharine Claman. David, as organizer of the event, brought two wild flowers of Bennington’s late spring that he had dug up and potted, a marsh marigold for me and blood root for Katharine, who nearly shared my birthday, hers being on the 28th. We have shared all our birthdays since and though we were just friends and not yet intimates for that first mutual celebration, every birthday since has reminded me of marsh marigold and blood root.

Why can I remember no other birthdays beyond the names of a few restaurants? They did not go uncelebrated. Another Japanese meal in Ithaca, New York with Katie Kazin, whose rare correspondences, including one for Katherine’s birthday this year, arrive by email from Jerusalem. Lunch at Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, which was our regular Saturday indulgence at the time. I know that there have been many strawberry shortcakes and many friends to share them all. There were no children when I turned 30 in Palo Alto, California, and three sons by the time I turned 40 in Litchfield, CT.

I think I will remember the tiny wine room at Picholine, an elegant New York restaurant where my parents hosted this year’s personal silver anniversary. It is not so many months since Bush the younger became a war-time President, but the Twin Towerless city is filling its restaurants again. There is still a table of pictorial hero and disaster books at Barnes and Noble near Lincoln Center, but the table is less prominent and the books are fewer.

I have never felt the need nor had the desire to mark birthdays in a major way, but I do enjoy a dinner with family a friends. If birthday’s provide an excuse for such gatherings, then they are occasions worth celebrating. But no birthday seems more important or “bigger” than another. I have pointed out to my children that if we had eight fingers instead of ten, the eights would be an excuse for more marked celebration. And if we lived on Mars, there would be a longer time between annual events. The progress of time may be inexorable, but the counting of it is a man-made convenience. For me, personal memories are fixed in time as much by events as by any sense of age. 20 years of school, marriage, births, and the different places I’ve lived hold greater importance than the mere achievement of a half-century of enduring.